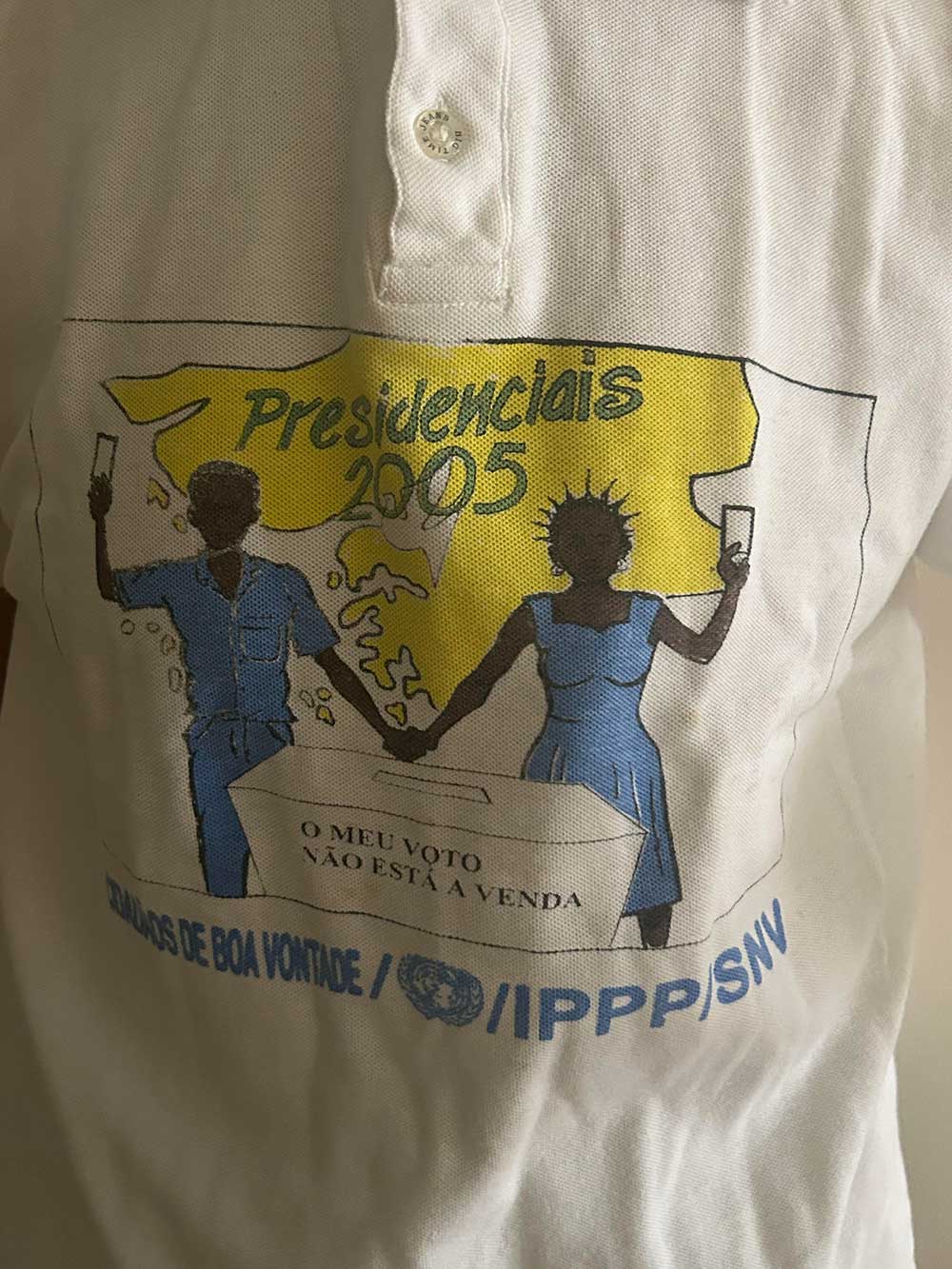

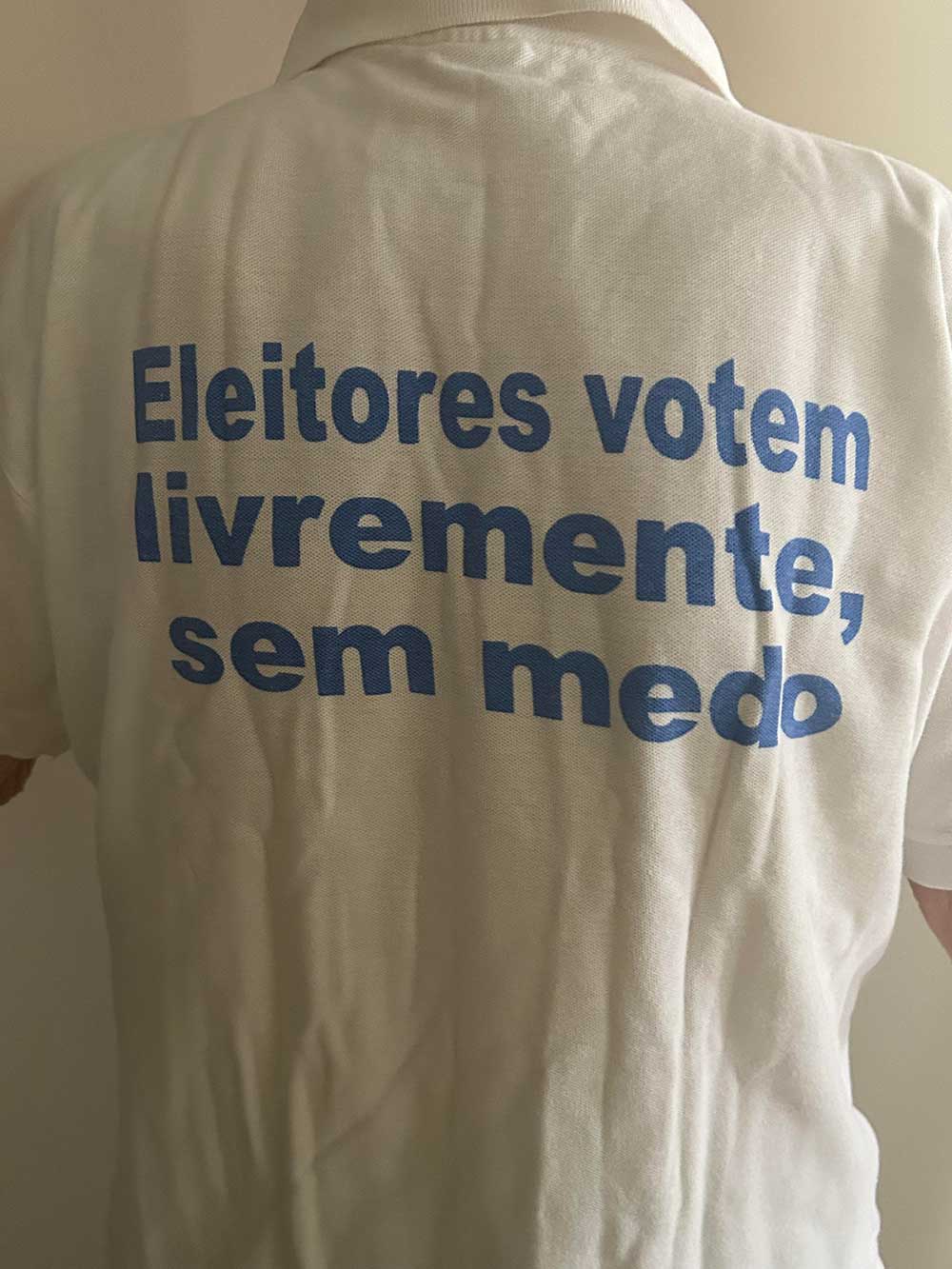

The tiny African country, Guinea-Bissau, had suffered a terrible civil war that destroyed much of its economy. Those who knew the country were certain that the national election in 2005 would trigger a renewal of the fighting. Well ahead of the election, an informal group of North Americans convened the heads of 10 civil society organizations and offered to help them if they wanted to work to prevent more violence. They responded enthusiastically. They mounted a campaign for peaceful elections using radio ads, T-shirts, large public banners, and person-to person messages throughout the country. On the event, there was no fighting in either the initial election nor in the consequent run-off. In the years since, the peace has held.

Guinea-Bissau

The tiny African country, Guinea-Bissau, had suffered a terrible civil war that destroyed much of its economy. Those who knew the country were certain that the national election in 2005 would trigger a renewal of the fighting. Well ahead of the election, an informal group of North Americans convened the heads of 10 civil society organizations and offered to help them if they wanted to work to prevent more violence. They responded enthusiastically. They mounted a campaign for peaceful elections using radio ads, T-shirts, large public banners, and person-to person messages throughout the country. On the event, there was no fighting in either the initial election nor in the consequent run-off. In the years since, the peace has held.

Based on that success, the Purdue Peace Project organized locally-led work to prevent threatened violence in about a dozen West African countries. In each case, local leaders responded enthusiastically. As in Guinea-Bissau, the local groups designed their own peace projects based on their knowledge of the culture, the people, and the specific situations. There were no failures!

Purdue Peace Project

The Purdue Peace Project is a university-based political violence prevention initiative that does peace-building work in areas threatened by such violence and conducts research to advance knowledge about political violence prevention at the local, community level. The cases highlighted on the website demonstrate how using local leadership can foster successful efforts

Purdue Peace Project

The Purdue Peace Project is a university-based political violence prevention initiative that does peace-building work in areas threatened by such violence and conducts research to advance knowledge about political violence prevention at the local, community level. The cases highlighted on the website demonstrate how using local leadership can foster successful efforts

INVOLVING OF LOCALS AFFECTED BY CONFLICT

Local leaders know and understand local situations, local cultures, and the local people involved in conflicts. Without deep understanding of local conflicts, foreigners are handicapped in their efforts to end them. Many have addressed the problems in the eastern Congo, but have failed to stop the fighting there. The small group of former fighters in South Kivu have demonstrated the value of the knowledge that comes from having lived for so long in a place.

The Carter School at George Mason University facilitated this initiative, funded by Milt Lauenstein.

Peacemakers have demonstrated many times that wars can be stopped or prevented, but violence continues.

We can assist local leaders in their efforts to bring peace to their communities.

SUCCESSFUL EXAMPLES

Encouraging stories

the cost of conflict

With the limited resources available to the peacebuilding field, focusing our resources on activities that are cost-effective will go a long way to determining the results we achieve.

Milt Lauenstein

Copyright 2023 © Less War.org | Powered by High Effect Web Design, New Hampshire.